UMCOR’s international work in suicide prevention

By Christie R. House

June 2020 | ATLANTA

Without water, there is no life.

Lilabai and her husband Ughde own about an acre and a half of land in Mahandula village, Beed District, in India’s Maharashtra state. They have two daughters and a son. Lilabai and her husband worked their small farm, but they couldn’t make ends meet, so they also worked as day laborers on other farms to feed their family. Even those efforts meant they were just getting by. Still, Lilabai raised goats, and the milk they produced and the opportunity to sell one now and then saved the family in difficult seasons.

Photo: CASA

For years, Beed District has experienced severe drought. The water shortage has left many subsistence farmers without food, employment or fodder for their animals. Poor rainfall in 2019 suspended agricultural activity for another season. Whole villages are deserted as families move to be near the big sugar cane plantations that offer work. These companies hire unskilled laborers, but sugarcane, 4% of agricultural production in India, also uses nearly 66% of the country’s irrigation water.

Beed is one of eight districts in Maharashtra where reservoirs are drying up. In fact, the reservoirs are down to 7% capacity. The government sends water tankers once a week to deliver water rations to thousands of residents across Maharashtra state.

Desperate situations

As each year brings delayed monsoon seasons and much less rain than needed, the situation becomes desperate for poor and rural residents. According to the People’s Archive of Rural India, this decades-long drought in Maharashtra has driven more than 60,000 farmers to commit suicide, with the rate averaging 10 deaths per day, as of March 2019.

Crop failure, followed by borrowing for seed and fertilizer for the next crop, only to have that season fail, means farmers have multiyear loans with no way to pay back mounting debt. In addition, their small land holdings, which no longer produce, become worthless.

Farmers like Lilabai and Ughde haven’t enough food and water for their families. Lilabai couldn’t buy fodder to feed her goats. Ughde traveled far to search for fodder, which affected his wages. He disappeared for days and left his children and wife behind.

India’s government opened fodder camps, where farmers could bring their herds for free fodder to help them survive, but the camps were only for large herds of cattle. Lilibai’s family is from the lower caste Dalit community, which raises small holdings of sheep or goats. With no other recourse, Lilabai was on the verge of selling her goats to feed her children.

The United Methodist Committee on Relief’s Sustainable Development department partnered with Churches Auxiliary for Social Action to identify marginalized people like Lilabai, who are on the edge of survival. CASA, an Indian founded and led community development and service agency of the National Council of Churches in India, used an UMCOR grant for a project targeting marginalized tribal and Dalit communities affected by farmer suicide across the Georai Taluka region of Beed District. The project offered drought mitigation and recovery programming.

Upon her community’s recommendation, CASA registered Lilabai for dry fodder distribution so she could feed her goats. The project’s timely support helped families in the community save their precious livestock, for many, the only asset they have left.

Learning a new way of drought-resistant life

In addition to supplying fodder, CASA also provided agricultural supplies for the next season, such as seeds and saplings, small tools and soil test kits. Young adults from the affected communities were hired to conduct surveys among their neighbors, collecting data to help CASA workers develop workable methods for recovery.

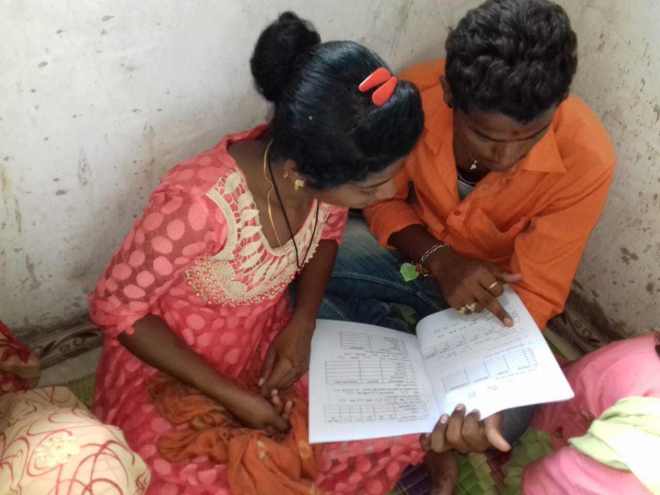

PHOTO: CASA

The project reached about 5,000 people in 10 villages. One way of reducing the rate of suicide is to bring people together in small groups for discussions about how to face the drought as a whole community, avoiding the isolation of families going it alone. CASA organized self-help groups among women, awareness programs, and it linked men and women across communities, developing broader farmer networks for support.

Women continue to meet regularly, and they’ve developed savings groups and small loan programs to support livelihood choices that depend less on climate and agriculture. The groups informed neighbors about government programs available to their communities. Sadly, many of the farmers who resorted to suicide would have qualified for government assistance, but they were unaware of what the government provided.

With support from the UMCOR/CASA partnership, Lilabai was able to save her goats, her children and her family’s income. Receiving the fodder for her goats provided just

enough hope for Lilabai and her family to hang on for better days ahead. Today, they are actively engaged in various programs of the project, and they applied for the government relief and recovery programs to which they are entitled.

Christie R. House is a writing and editing consultant with Global Ministries.