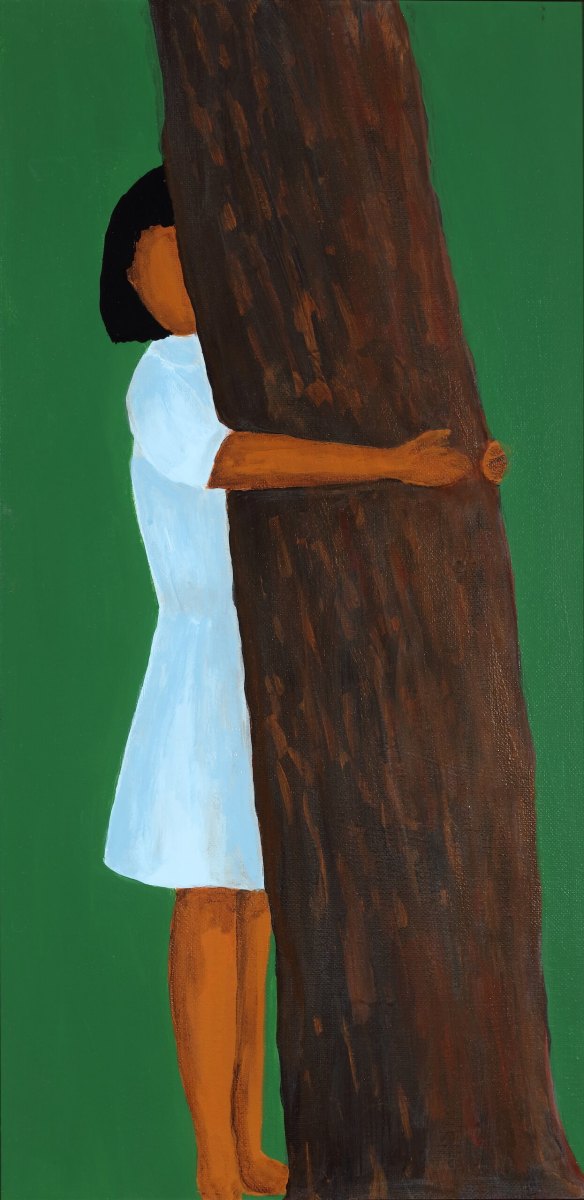

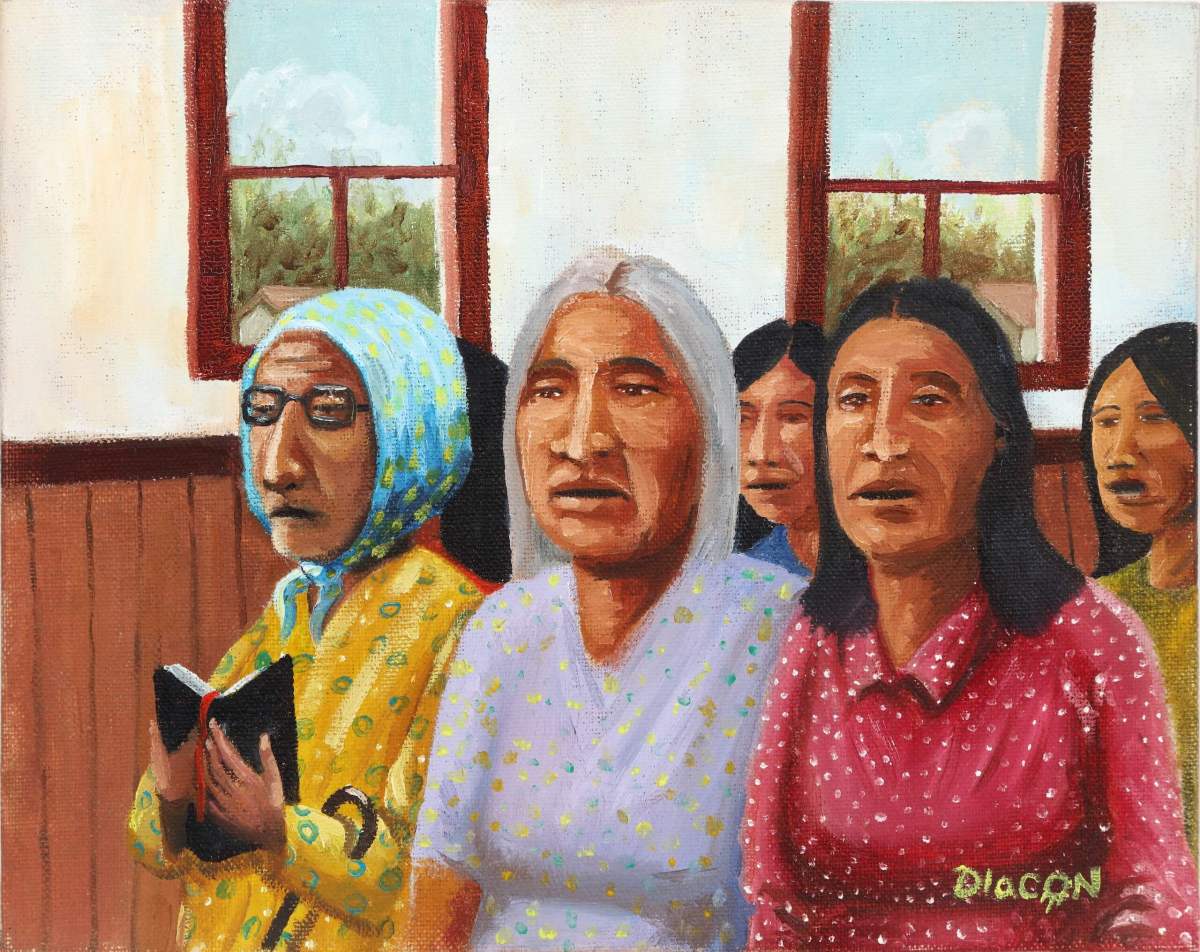

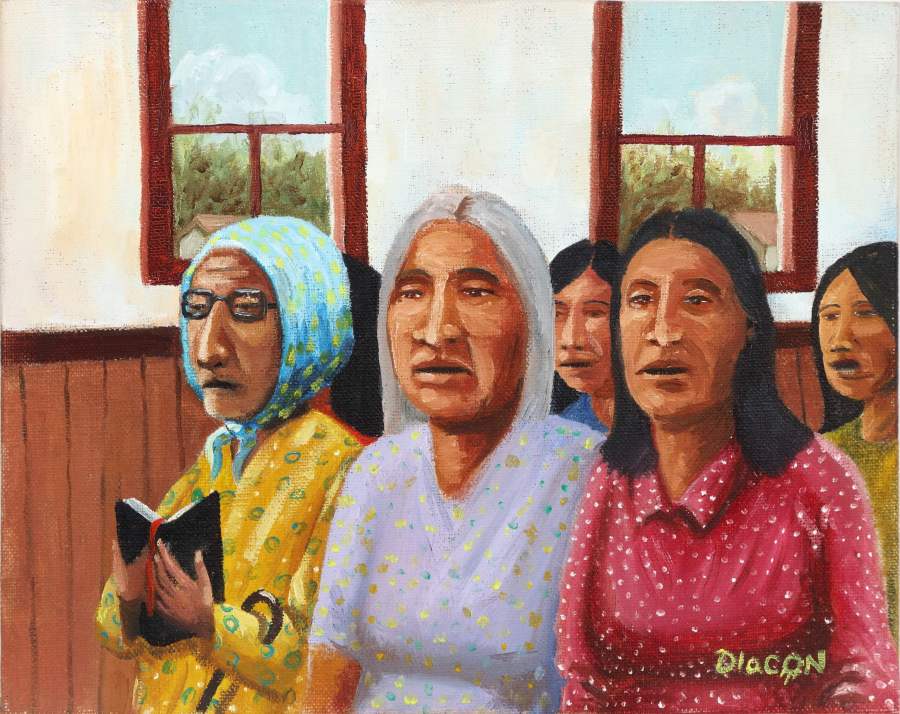

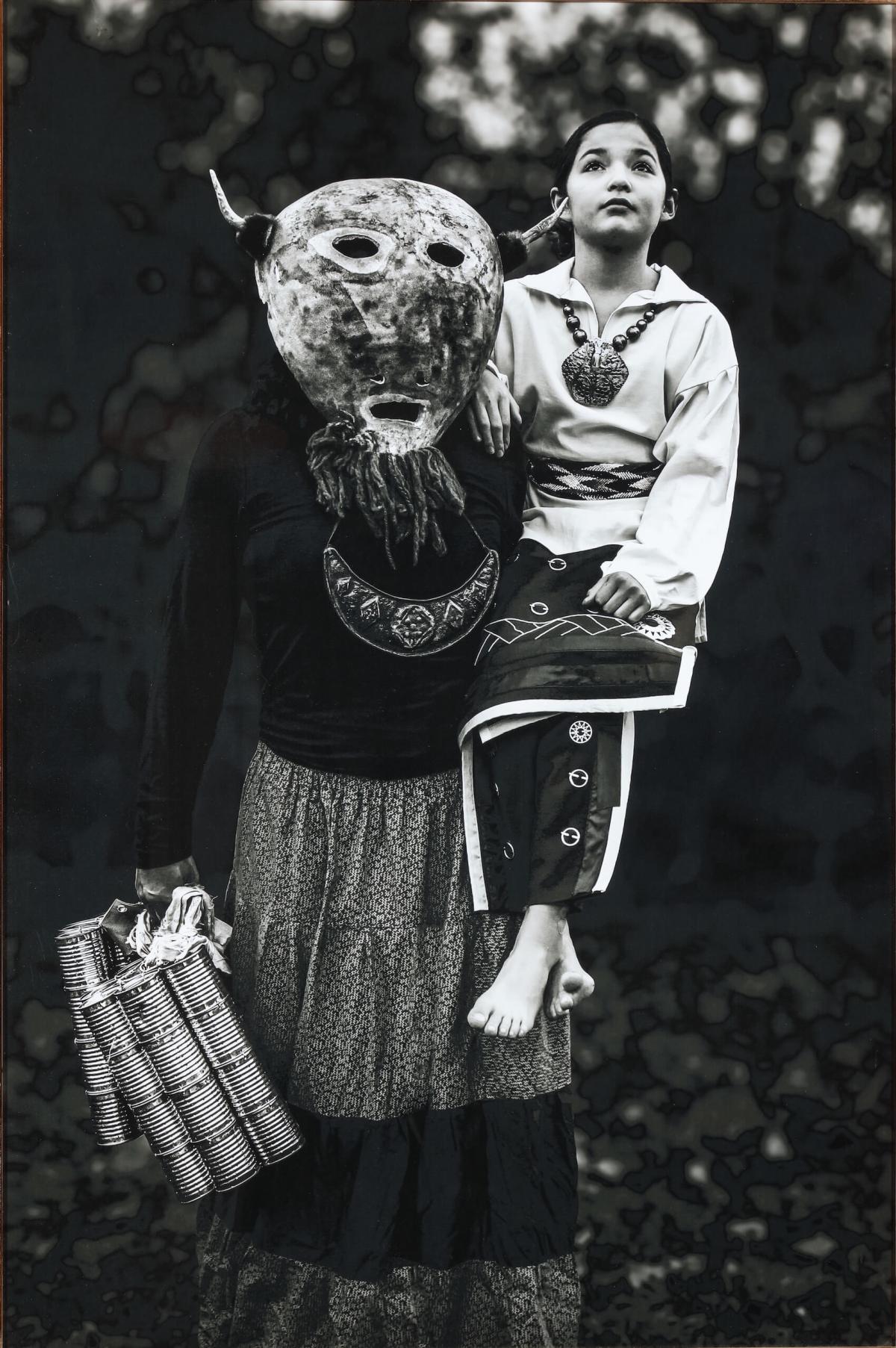

The art forms in “Identity & Diversity” reflect the struggle of Southeastern Native Americans to maintain their deeply rooted identity with their diverse backgrounds in the face of mainstream culture that often does not recognize their presence. Although Southeastern Indigenous culture is often obscured by Native American stereotypes, here the artists give a face to their people and tell us who they are through their visual works.

The majority of Indigenous Americans now living in the Southeastern U.S. have Mesoamerican ancestry, many of which have come to the region in recent times. While it has been asserted that the first peoples of this region came from the same origins, the featured artists have had ancestral roots in this region for millennia. However, their descendant tribes became multiracial and multicultural after contact with Europeans (mostly arriving by choice) and with enslaved Africans.

Other works in this section reflect how with assimilation of nonNative cultural institutions came the exploitation of land and labor and secular and religious incursion into Indigenous homelands. With increasing federal support for Southern states resistance of Southeastern tribal autonomy came the pivotal Indian Removal Act of 1830. It led to subsequent homeland removals which had a lasting impact on Native identity but was traumatic for nonNative peoples as well.

Decades after removal to Indian Territory, now Oklahoma, the Indian boarding school program, addressed in this section, became a means to erase Indigenous identity. Even in recent times, internal issues of belonging are slow to be addressed within Southeastern tribal nations such as Black Native Americans who still await promised tribal citizenship. Meanwhile, an increasing number of nonNatives erroneously claim tribal ancestry, further eroding Indigenous identity. Yet, first peoples of the Southeast are increasingly making themselves known even in their homelands.