Highlights

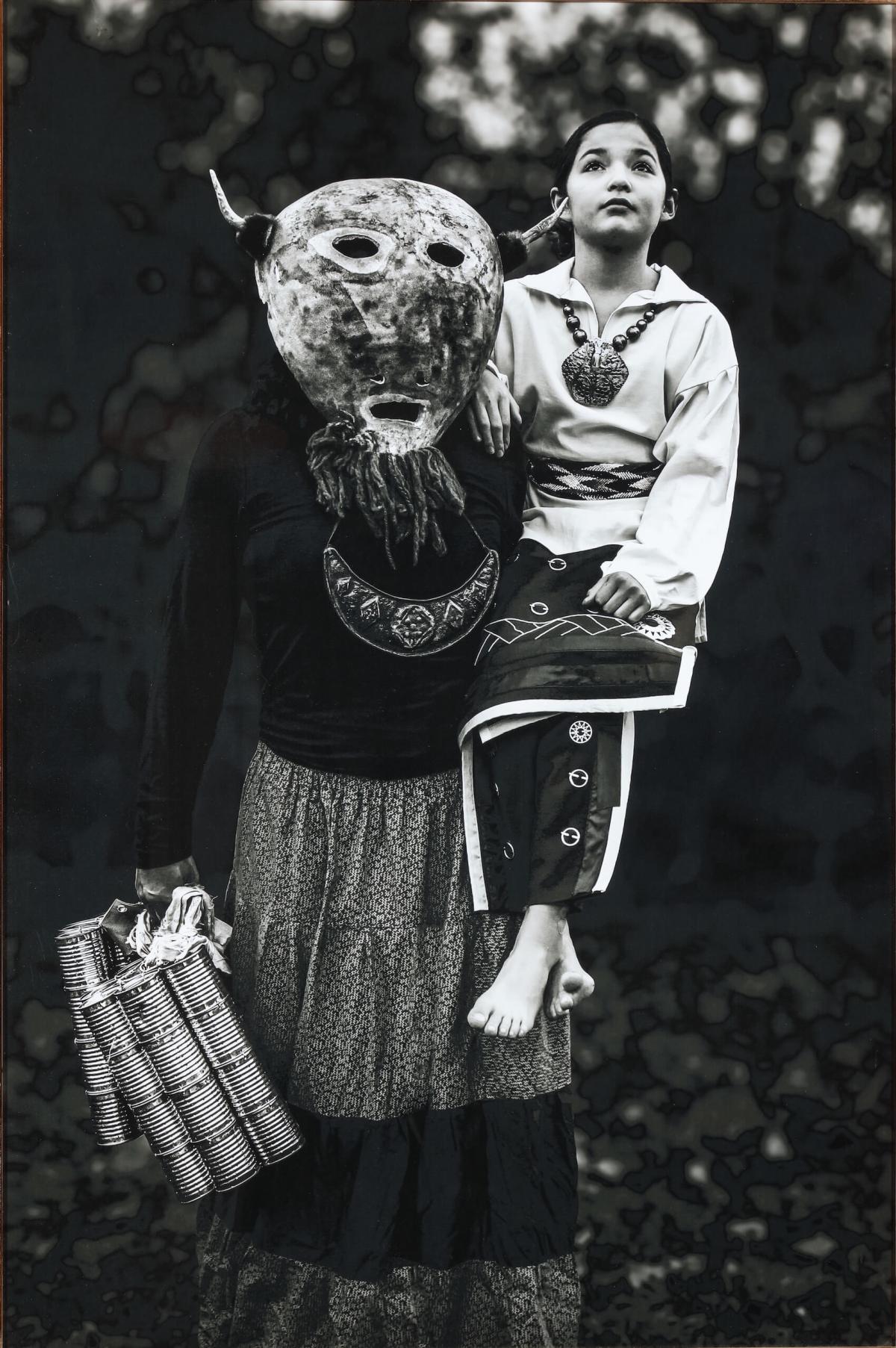

Kristy Maney Herron

Cherokee, Eastern Band / Dine’

Little Sisters of Resolution, 2017

In this photograph Kristy Maney Herron documents the teamwork and resolve of two young girls at a lacrosse camp in Cherokee, North Carolina. The camp is led by Native American players of the Georgia Swarm (an Atlanta-based professional lacrosse team). Lacrosse is a little “sister” of the older game of stickball, traditionally played by men with no padding. It was popular in the Southeast long before football and playing fields became an integral feature of towns and villages. Long ago, stickball was part of warrior training and became known as “the little brother of war.” More than a game, the contest was used by Native peoples in the Southeast as a way to resolve tribal conflicts, also called “stickball diplomacy.” Historical accounts indicate that Cherokees won a territorial war with Muscogee Creek in the 1700s by defeating them in a stickball contest, which took place at present-day Ball Ground, Georgia, just north of Atlanta.