Highlights

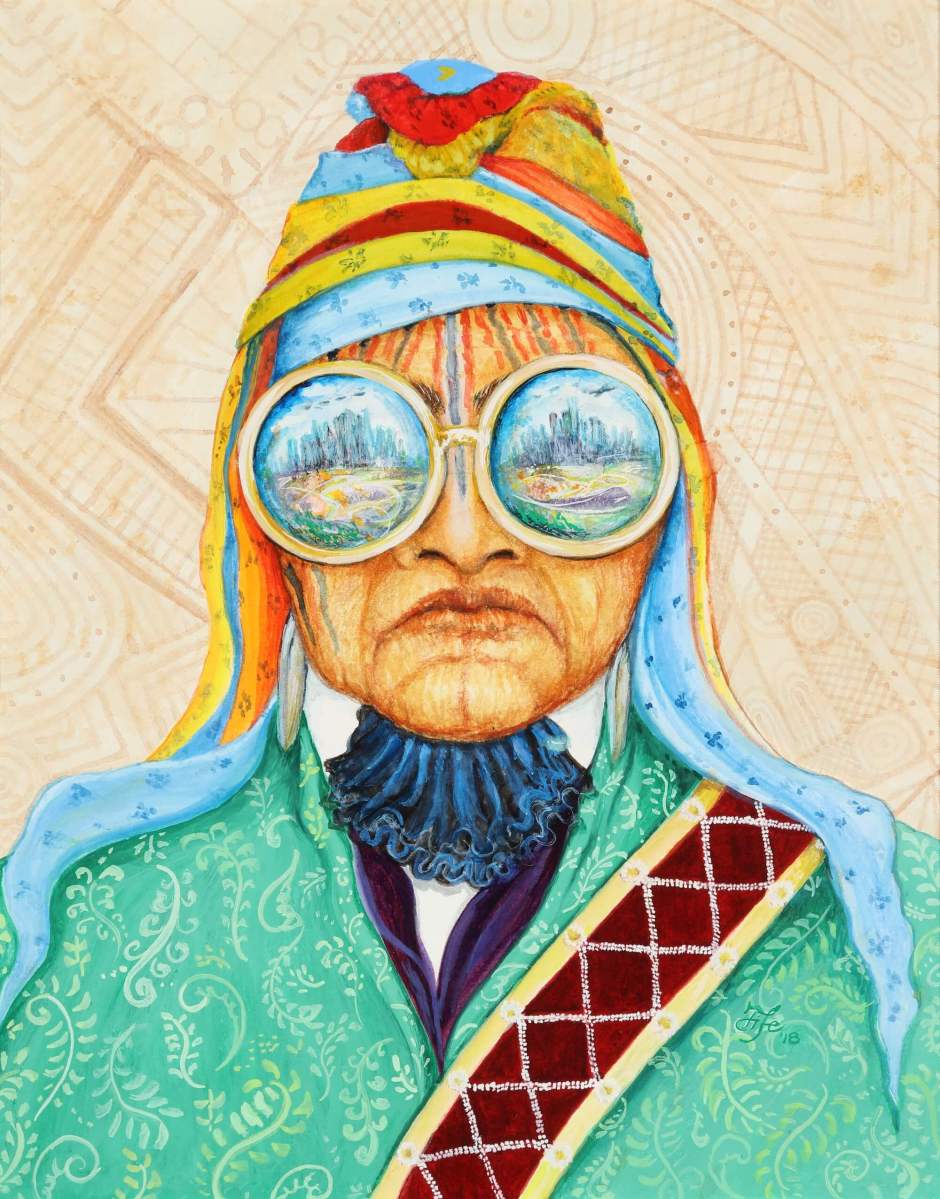

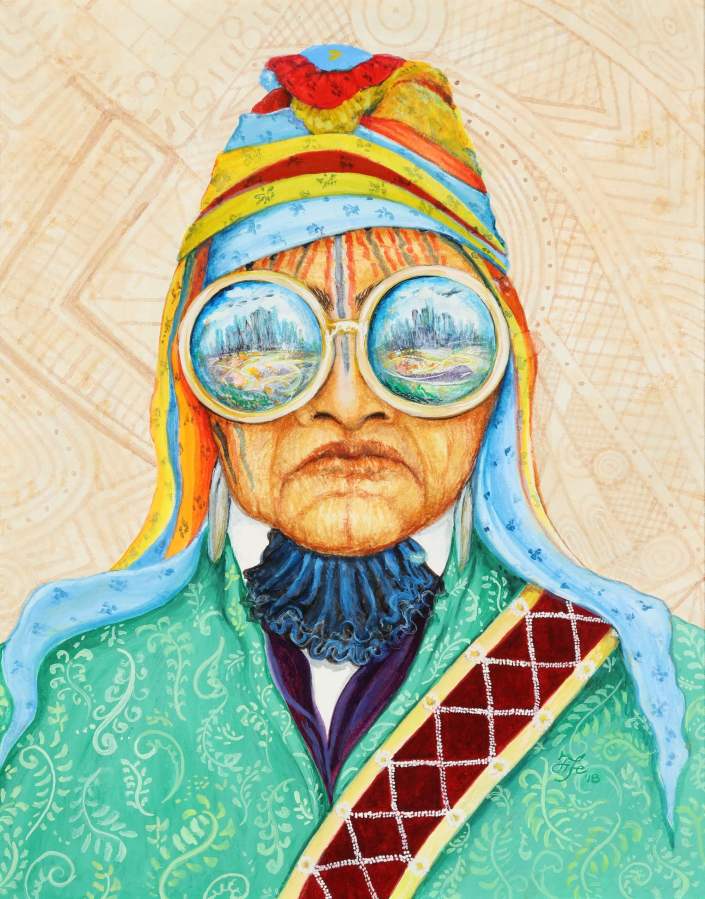

Jimmie Carole Fife

Mvskoke Creek

I See the Future, 2010

In Jimmie Carole Fife’s work, I See the Future, a man in Muscogee (Creek) attire of the early 1800s sees a future world through prophetic glasses with images of his tribe’s ancestors behind him. Together, the figure and background represent the legacy of the Mvskoke as people of vision and voice. The subject is based in-part on a portrait of Yoholo Micco (Upper Creek Chief of Eufaula) made in Washington City after he protested the 1825 Treaty of Indian Springs. It was an illegal land deal made between the U.S. and Muscogee leaders under Tustunnugee Hutke (Lower Creek Chief William McIntosh). Yoholo’s resistance to selling tribal land stands in contrast with his “farewell address” to the Alabama Legislature in Tuscaloosa before Creek removals to Indian Territory in 1836. The tone of the written account of the speech is so conciliatory that its accuracy and authenticity have been questioned. Despite the loss of homelands, Yoholo Micco foresaw a bright future for his people. Its seems fitting that a trail in Eufaula, Alabama was named for him and that the artist’s brother, Bill Fife, was a recent Principal Chief of the Muscogee Nation in Oklahoma.