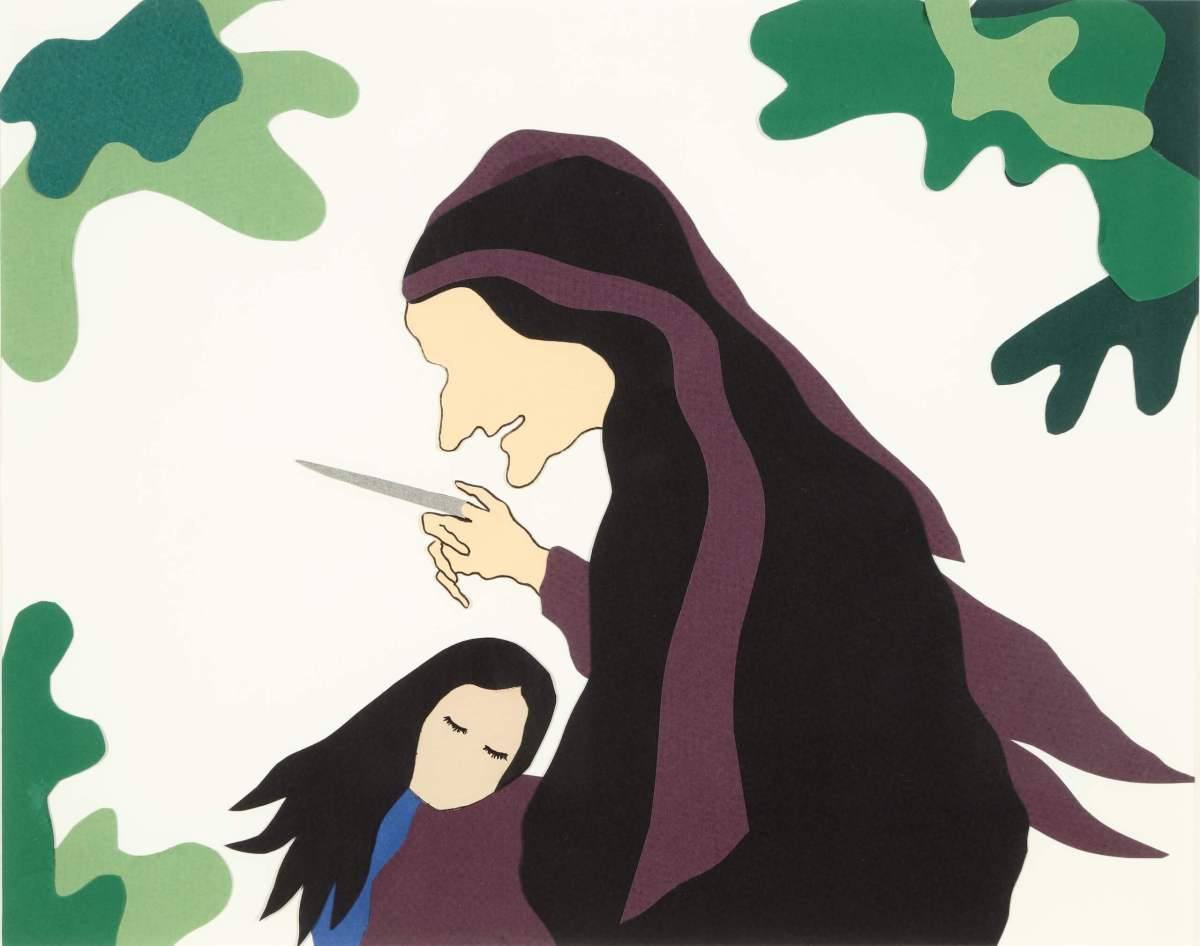

Highlights

Luzene Hill

Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians

Starting Harvest Bonfires, 2007

A native of Georgia, Luzene Hill started her art career in Atlanta at mid-life. When she moved to Western North Carolina in 2006, she began a project with Cherokee (Tsalagi) speakers to create a book for a Cherokee studies course. The language was not passed down to her from her father’s parents since it was forbidden at their Indian boarding school. Hill says, “Indigenous languages reflect a distinct worldview, including what people value: their culture, cosmology, healing practices imagination and humor.” She was also commissioned to illustrate the story of Spearfinger, a mythical creature in Cherokee lore from the Smoky Mountains region. By changing into a familiar old woman, Spearfinger would lull village children to sleep only to unveil her pointed index finger. The illustration shows fires being set in autumn to clear brush and harvest fallen chestnuts. The rising smoke that provided a way for Spearfinger to find nearby villages led to its demise as the local townspeople set the fire to draw the creature into a trap.